Upcycling, a History of an (anti-)fashion technique? by Emma Pédurand

More than a sustainable way to produce clothing, upcycling implies both a political and aesthetical shift in consumption patterns: consuming less, reusing more, accepting and cherishing imperfections in the craft.

Upcycled Pieces by Tata Christiane

From scarcity to abundance: upcycling across the ages

A practice old from the dawn of times

Opening our gaze to the anthropological perspective could help us acknowledge the meaning and purpose of upcycling. This technique is neither a modern nor a Western cultural invention. Anthropologists argue that upcycling has always existed among human societies, especially in ages and places of scarcity: “When the first prehistoric people inhabited the earth, their crafting of tools from flints and bone or the fashioning of shelters from local vegetation was a kind of upcycling.

Clothes by Fade Out Label – Photographer @0h___hi___mark – Muse @jembosatta

In many parts of the world, millions of people with very limited resources practice the creative reuse of other peoples’ waste as a means of survival”*. In Western modern societies too, the majority of people were to mend and repair much-used items of clothing until the development of the ready-to-wear industry in the second half of the 20th century.

*Amick, Daniel S. The Recycling of Material Culture Today and during the Paleolithic. Quat. Int. 2015, 361, 4–20.

Photographer: Nicole Fiser @nikifiser

TALENT: Lafayette Vanderkin-Jus @lafayettevanderkinjus

MUA & HAIR: Xoana Vicente @chinavicente

STUDIO: Allmost Studio Berlin @allmostudio

Styling: Angie Aguirre @slave_2_words + @poli_aguirre

All items are @therapy_berlin

Upcycling in a society of abundance

If upcycling as always existed, why does it seem so minor in today’s fashion landscape? One reason lies in the fact that fashion industry represents a stable source of prosperity for capitalistic organizations. While the emergence of the consumer society in the 20th carried the deceptive promise of a wider access to wealth and abundance, one contemporary is hit by the sorry reality: 8000L of water are needed to produce one single jean and 2 to 3 billion of them are bought each year in the world**. And people only wear an average 40% of what they buy***.

Clothes by Fade Out Label – Muse @crazy.leather.berlin

Using scarcity as a resource

The development of mass production was only slowed by the shortages due to the two world wars – see for example the ‘make-do-and-mend’ governmental campaign in the UK. After World War II, the slogan ‘making new from old’ – propagated by German officials during both wars – was very successful in the GDR’s society, where “women enacted this motto by ingeniously transforming everything from old clothes, rags, and tablecloths to parachutes, uniforms and military bed sheets into “new” patchwork dresses (Flickenkleid) or shirts”.

Upcycled Football Jumpers by Tata Christiane

A socialist heritage

In capitalistic countries, slow fashion is a political statement which could be interpreted as a remnant of the socialist standpoint against fashion. During the Cold War indeed, “Anti-fashion East German Marxists claimed that capitalists deliberately stimulated the “unreasonable fickle moods of fashion”, as Marx had called them in Capital, and used them to manipulate the masses, to create “false” needs for new clothes, and thus to increase corporate profits”****. Slow fashion initiatives aim to free individuals from their enslavement to fashion and discourage them to follow the insane pace of leading capitalist brands.

Photographer: Nicole Fiser @nikifiser

TALENT: Lafayette Vanderkin-Jus @lafayettevanderkinjus

MUA & HAIR: Xoana Vicente @chinavicente

STUDIO: Allmost Studio Berlin @allmostudio

Styling: Angie Aguirre @slave_2_words + @poli_aguirre

All items are @therapy_berlin

A trend like no other?

The paradox of a sustainable trend

Two parallel and contradictory phenomena can be observed in the contemporary system of fashion. On the one hand, trends are being propagated and renewed faster and faster, when on the other hand, new generations of designers promote a fairer and more sustainable way to make fashion, in which the productive reuse of discarded materials and worn-out clothes — called “upcycling” — appears as a favorite technique.

Unique Pieces by Tata Christiane Photography: Magdeleine Dechelette and Julie Roubinet

Model: Liesa

The word “Upcycling” arose by the late 1990s, in a context of concerns regarding environmental damage caused by mass production. It is now agreed that slow fashion is the only alternative to fast fashion retailers and the ‘take-make-waste’ economy. Considered that “consumption is derived from the French consumere – to take up completely, devour, waste, spend”*****, upcycled items cannot be considered as properly consumed. Instead, they drive our attention towards the core artistic and emotional value of each piece of clothing.

Clothes by Tata Christiane – “Baroque Pourquoi pas” collages by GSant – Model: Karin

Distinctiveness without imitation

Following Georg Simmel, upcycling could hardly be described as a trend. The German philosopher demonstrated that fashion necessarily encompasses both the individual need for differentiation and the inevitable tendency to imitation (Die Philosophie der Mode, 1905). Upcycled garments however, as unique pieces, cannot result in recognizable patterns and give way to the generalization of a trend. But Simmel makes a further interesting point: claiming oneself as a fashion outsider is nothing but a negative way to state one’s awareness of and belonging to the fashion system. The individualistic spread of uniqueness as a style mantra – especially among millennials – should then be reckoned as a fashion movement.

Clothes by Fade Out Label – Photographer @athena_paras – Muses @mypunksnotdead2 @mjfromyourblock

The beauty of the accident

Less perfection, more life

In a society of abundance, finding resources in existing garments is a good way to come up with original aesthetical forms. Assembling pieces that were not meant to be assembled enables to create new meanings and pay attention to the beautiful accidents that may arise in the process. Just like dreams, upcycled designs can’t suffer any control.

Film: Elisa Cucinelli

Fotos: Sabrina Knierim

Music: Elliot Fouchy

Costume: Tata Christiane

Model: Sabrina Hubert

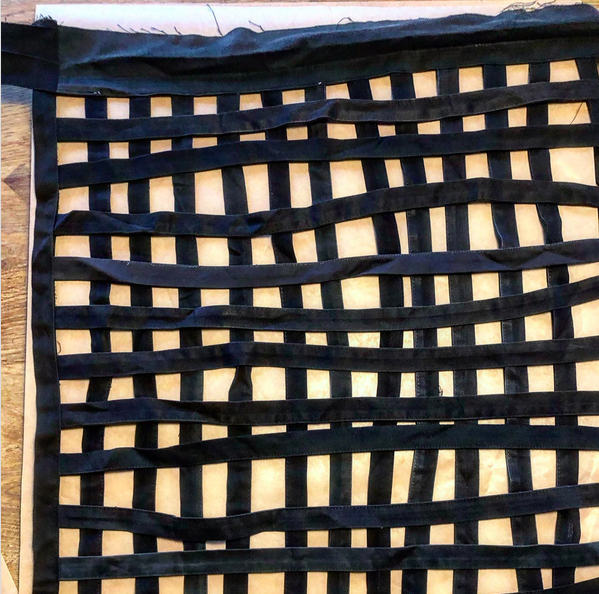

design by Victoria Ladefoged – The Net Dress

Those unique creations convey secret messages waiting to get unfold. Instead of longing to acquire more and more material means for creation, designers should consider alleviating resources as a chance of relief and an occasion for renewal: « In other cultures, such as the Japanese ‘wabi-sabi’ aesthetic which celebrates ‘the beauty of things imperfect, impermanent, and incomplete’ (Koren, 2008), [the] inconsistent supply of materials would be seen as a source of inspiration and serendipity.»*****

Workshop by Tata Christiane at DEN SKANDINAVISKE DESIGNHØJSKOLE MARCH 2018

Emma is a young visual artist & a sociologist currently writing her thesis on the dynamic of Berliner fashion design. She is open to collaboration with researchers and designers.

You can contact her via email (emma@pedurand.com) or Instagram: @emmapedurand.