What makes Berlin a fashion city?

by Emma Pédurand

Berlin has been welcoming a fashion week twice a year since 2007. The Berlin Fashion week promotes the capital as one « that serves as a dynamic muse and a catalyst for pushing the boundaries of fashion, embracing inclusivity, sustainability, and a bold, avant- garde ethos » . How is that so?

A fire inside an Italian restaurant in Schöneberg.

A fire inside an Italian restaurant in Schöneberg.

A one-of-a-kind cultural capital

West-Berlin was designated a European Capital of culture in 1988, one year before Paris. As a cultural capital, Berlin stands out for the dynamism of its creative scenes. Contrary to other well-established European cultural cities like Paris or Florence, Berlin doesn’t owe its reputation to its monuments and institutions, but rather to its cosmopolite appeal and informal urban spaces for creation. Since the early 20th century, and even more so since the Fall of the Wall, Berlin can be regarded as a « heterotopic » city blurring the boundaries between the real and the imaginary, where utopias can unfold and thrive. In the 1920s, the English writer Stephen Spender wrote that Berlin ‘seemed a paradise where there was no censorship and young Germans enjoyed extraordinary freedom in their lives’ (Page, 1998, p. 39 — quoted by Andrew Thacker, “‘Hellhole and Paradise’ : The heterotopic spaces of Berlin”). Berlin was already a very inspiring city with few constraints for artists. Sexuality was less normative than anywhere else in Europe — Stefan Zweig named the city ‘Babylon of the world’ due to its sexual openness. During the Cold War, West-Berlin was the first city to have such a broad gay scene and community. This sheds light on why fetishist fashion as a symbol for freedom remains so bound to the cultural identity of Berlin.

Berlin has remained a place where utopias can unfold and thrive.

A garland of bell peppers and eggplants in a Bulgarian restaurant in Neukölln.

A garland of bell peppers and eggplants in a Bulgarian restaurant in Neukölln.

The city for avant-garde artistry and techno-fashion

The vibrant heart of artistic West-Berlin, Kreuzberg, still surprises by the variety of its urban landscapes and graffitis. If the very idea of fashion is intrinsically linked to modernity, the Berlin fashion represents the lucid affirmation of confusion in a world where systems no longer rule individual life choices and appearances. In that sense, fashion in Berlin is so diverse that it can barely be called fashion. Just like techno parties invite a set of individuals to attempt to reach a spiritual bond and the overrun of individualism, we could call « techno-fashion » the grouping of diverse visions of fashion coexisting in harmony and appealing to every taste (good or bad) while hoping for the implementation of a transcendent, genuinely communal fashion. That intent to unite the irreconcilable recalls the experience of the Deutscher Werkbund, a society of artists and architects created in 1907 that claimed that the industry should work hand in hand with the arts to bring technology to aesthetics, in the wake of the Arts and Crafts Movement.

A bike store and a circus at the Görlitzer Park, Kreuzberg.

Earlier than anywhere else, art and design were invested as social-critical fields in Berlin. During the Weimar Republic, while corrupted bourgeois were running the country, artists from all over Germany and Europe flew to Berlin and experienced there a state of radical openness and liberation from traditional norms and aesthetics. Several movements arose in those years, such as Expressionism (Der Blaue Reiter, by Kandinsky and Marc) and the Bauhaus school for art and design founded by Walter Gropius, which motto was in 1923 “Art and Technology: A new unity”. Those avant- gardes have influenced Berliner fashion up till now: the Berlin fashion sphere can be roughly divided between a fashion that puts the emphasis on its expressionism and queerness, and one that rather claims its technological, functionally innovative aspect. The role of music is paramount in the reshaping of Berlin fashion trends.

Franz Marc, « Die gelbe Kuh », 1911.

Franz Marc, « Die gelbe Kuh », 1911.

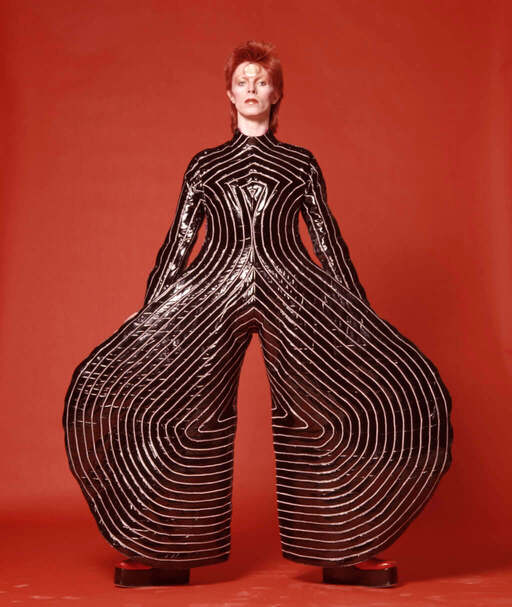

The 1970s pop-rock scenepaved the way for an unbridled fashion empowering unique personas, as symbolized by Davis Bowie’s costumes. The 1980s punk style, that gave Kreuzberg its identity and that inspires Tata Christiane designs, enabled transgression and the liberation of the female body. The 1990s techno culture then aligned with postmodern aesthetics, ranging from grotesque elements to all-black anonymous looks.

Technology as well as minimalistic Bauhaus aesthetics and the ever-living heritage of the pop culture can be considered as main inspirations for contemporary Berlin Fashion designers.

David Bowie dressed by Yamamoto, 1973. Photograph by Masayoshi Sukita.

David Bowie dressed by Yamamoto, 1973. Photograph by Masayoshi Sukita.

A city of postmodern oddness

In winter, the heart of the city beats in indoor secret places. The fashion world recharges its batteries in the intimacy of private rooms, cafés and in the underworld, preparing to bloom as soon as the nature will regain vitality. Fashion is fueled with the imaginary of the seasons, and winter in Berlin feels like a frozen time where urban life partakes of the dream and the tale. This specificity is important to understand the disruptive energy of the Berlin fashion, bringing life back to the monotonous winter while underlining its odd reality.

A young woman in Autumn on Unter den Linden, Berlin-Mitte.

A young woman in Autumn on Unter den Linden, Berlin-Mitte.

One thing that struck me when I arrived in Berlin was the communal aspect fashion took here. The youth seemed to be striving for a sense of belonging through values such as feminism, tolerance, cosmopolitanism and ecology. This search is made visible through fashion. At stake is the need to feel in tune and involved in a group of like-minded people with dreams and hopes alike. All of them are questioning the meaning of life in a society where scarcity is no longer an issue. Indeed, in advanced industrial societies like the German one, a shift occurred from materialist values to post-materialist ones towards the end of the 20th century.

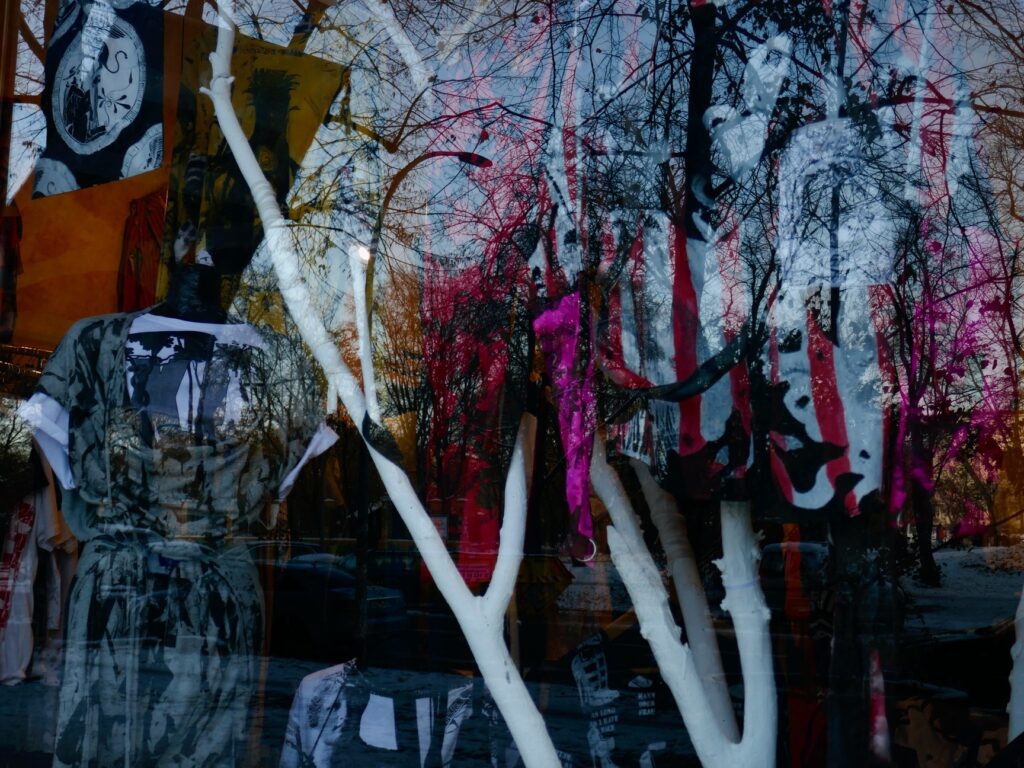

The window of a punk shop in Berlin-Kreuzberg.

The window of a punk shop in Berlin-Kreuzberg.

« Though still interested in a high, material standard of living, [people living in advanced industrial societies] take it for granted and place increasing emphasis on the quality of life. Though economic growth is still valued, an increasing share of the public is willing to give environmental protection priority over economic growth when they conflict. » (R. Inglehart, 1999, « Globalization and postmodern values »).

As it was directly affected by the collapse of the USSR, Berlin seems like a city of the after-world, embodying the climax of postmodern values.

Walls in Kreuzberg.

Walls in Kreuzberg.

As a city of the ephemeral, endless motions and not-to-be-continued encounters, Berlin aligns with the essence of fashion, which is to praise the beauty of the instant without any hope for its continuation. A space virtually enacting hedonism. No boundaries are to be encountered here, nothing but weirdness, grotesque, absurdity, irony. This perception is at the core of Tata Christiane designs.

A case can be made that Berlin adopted the postmodern worldview earlier than other industrial cities, at the end of the communist era. There was an urge to fight against the capitalist expansion after the reunification in order to save spaces for freedom and creation inside the city. The protection of the Tempelhofer Feld as a virgin green space in spite of the will of the government to turn it into a commercial area can be seen as the symbol of the triumph of postmodern values over the traditional industrial ones. The alignment of such values with the economic necessity helps to understand why Berlin was a pioneering city for ecological fashion.

What unites most Berliner fashion designers nowadays is their commitment to a fairer and more inclusive fashion. In Berlin, fashion appears as the physical enactment of political and philosophical convictions. Tata Christiane stands for an expressionist and cheerful vision of fashion, where the colors and shapes of clothes speak for the soul of the person who wears them. Tata Christiane was the first Berliner brand to use upcycling and therefore set an influential movement that keeps on shaping Berlin’s fashion environment today.

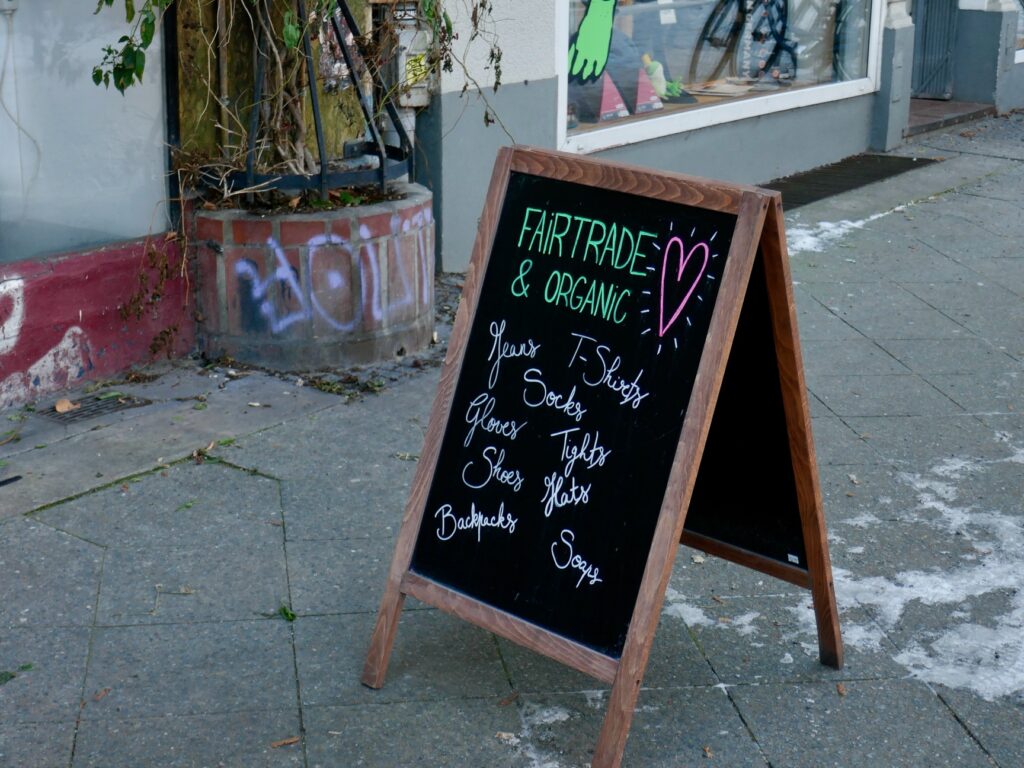

At the entrance of a fair trade clothing store in Kreuzberg.

At the entrance of a fair trade clothing store in Kreuzberg.

Advocating for fantasy, individuality and fun clothing, Tata Christiane’s fashion makes the most of the creative potentialities of our postmodern society.

Charles Baudelaire said « Beauty always has an element of strangeness ». Berlin shows that strangeness always has an element of beauty, and it belongs to fashion to make this truth visible.

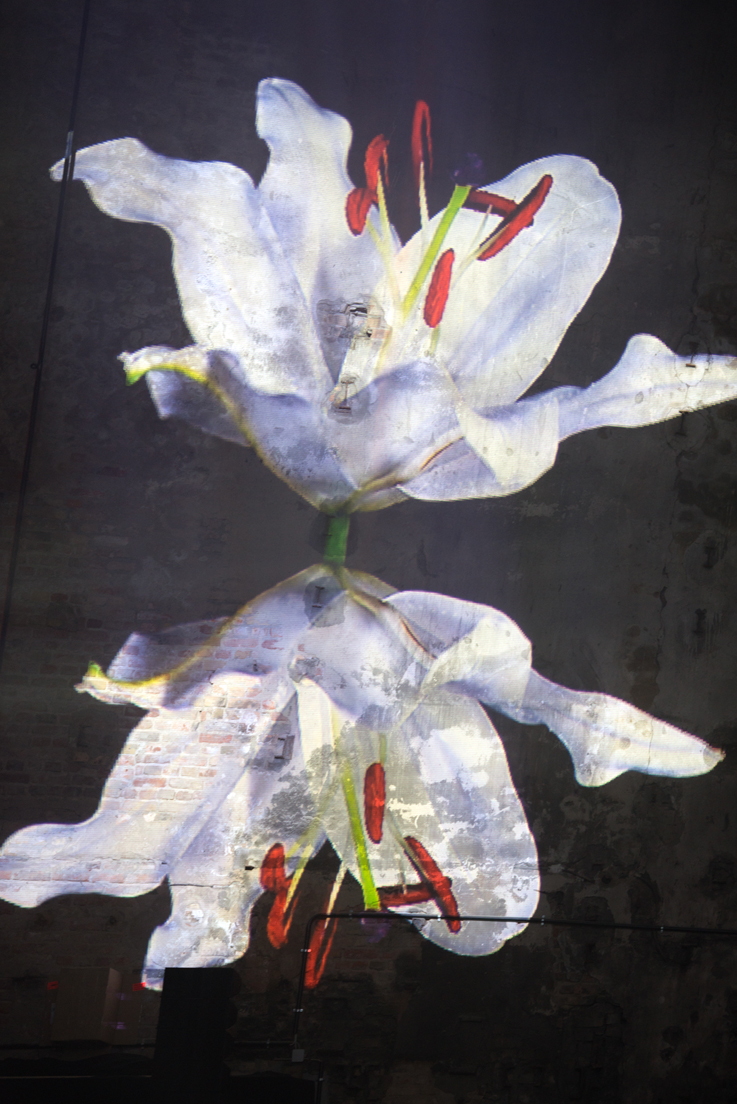

“Utopie aléatoire”, Unique pieces Collection SS17 at Berlin Alternative Fashion Week, Kantine am Berghain. Photography by Peter E. Reiche 2017

Emma is a young visual artist & a sociologist currently writing her thesis on the dynamic of Berliner fashion design. She is open to collaboration with researchers and designers.

Emma is a young visual artist & a sociologist currently writing her thesis on the dynamic of Berliner fashion design. She is open to collaboration with researchers and designers.

You can contact her via email (emma@pedurand.com) or Instagram: @emmapedurand.