L’Enfant Azur: Between Neuroatypia, Inclusion, and Artistic Creation, by Amandine Habid

1. Article origin: Conversation with a friend from high school

1. Article origin: Conversation with a friend from high school

2. Nine Spirit: Hybrid projects and OANI

3. Balancing roles: Life, creation and motherhood

4. Change in 2015: a new artistic dimension

5. Confronting difference: Journey with my son

6. Inspiring encounters and crucial support:

– Parent training: Key to understanding autism

– The family circle, a shared struggle

7. Festival Piano en Fleurs: Neuro-atypical inclusion

8. Genesis of “L’Enfant Azur”: Inclusive show

9. Reflections on the meaning of commitment and Autism

– Commitment: another form of modesty

– Autism and the experience of the Other

10. Embodying the creative project: voice and bodies

– Moonk, voice and body

– Angel and Vito, bodies and dance

11. The interdisciplinary creative residency

12. The first performance of L’Enfant Azur in the Jardin de Fontblanche in Vitrolles

13. Conclusion: Dreaming, laughing and accepting singularity

14. About Amandine Habib

1. Origins of the article: Conversation with a friend from high school

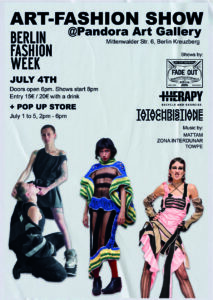

The inspiration for this article came from a conversation with a long-time friend Julie Bourgeois, the founder of the fashion label Tata Christiane.

The inspiration for this article came from a conversation with a long-time friend Julie Bourgeois, the founder of the fashion label Tata Christiane.

We were two rather original kids at Lycée Thiers. Julie was sewing and I was playing piano at the Conservatoire. First, she made stage dresses, a bonnet, and lots of laughs along the way.

As adults today, I realize that what we might have called originality in the past has actually never left us and has become the bedrock of our shared future.

2. Nine Spirit – Tata Christiane: Hybrid projects and OANI

Tata Christiane’s couture is deconstructed yet joyful, for queens or punks. It resembles many of the projects I carry and defend.

The projects of the Nine Spirit company, of which I am artistic director, are also aimed at everyone. They are hybrid in form, often transdisciplinary and trans aesthetic.

We could call these projects OANI: Objets Artistiques Non Identifiables.

These definitions of our artistic choices fit perfectly, if I may say so, to what neuroatypia is a rather different way of being in the world.

“Azur does a lot of things that go against the grain, but which way are we talking about? The way people usually go? This child isn’t interested in the straight-and-narrow direction of everyone else.”

But back to L’Enfant Azur and its origins.

3. Balancing roles: life, creation and motherhood

I used to compartmentalize and separate my brains. I am a classical pianist, project creator, artistic director of the Company Nine Spirit; an artistic director of the Festival Piano en Fleurs and teacher; a the mother of two children.

Why have I differentiated these little worlds so much? Perhaps so that the universe of each little sphere, built up and tied up like a roast, doesn’t overflow and drip onto another part of me. And there’s always this underlying fear that imagines that one facet could annihilate or devour another.

Probably also because in artistic circles (and in all professional circles), the difficulties, fatigue, and day-to-day concerns of motherhood have long remained fairly taboo subjects, even if tongues have recently begun to loosen.

Being a mother and looking after children were seen as an obstacle to career advancement. It was also seen as a way of preserving the idea that we are equally productive and creative at all stages of our lives.

4. Change in 2015: a new artistic dimension

In 2015, a new page was turned: I became a mother, and despite or with this, my artistic activity continued to be enriched by new encounters and new projects. The thread I’d started to pull so long ago was unwinding differently, but perhaps more powerfully, more focused.

My relationship with time changed with children, but I was enriched by this metamorphosis.

5. Confronting difference: My journey with my son

Then I was confronted with my son’s difference.

First, there were the words ASD – Autism Spectrum Disorder – and ADHD – Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder.

Little by little, I realized that I had to train myself if I wanted to help him.

Little by little, I realized that I had to train myself if I wanted to help him.

This difference has certainly been hard, sometimes violent, and has caused a lot of sadness and anxiety at times, but it has also been a gift. This singularity makes us reflect on the concepts of normality, and questions our way of seeing the world, sometimes with a great deal of humor.

Along the way, we discovered all the walls we come up against. The school, which doesn’t have enough resources, the reflections of others, the slowness and weight of the administration and institutions, society, which is not yet ready and educated to open its eyes and its heart to neuro atypia.

Against these walls, and the other difficulties in our daily lives, I had found a method to keep me standing tall and strong: diving into the sea without a wetsuit whatever the season, and then the rage would subside.

I’m sure of one thing today. The sea washes away anger and sadness from the brain and soul.

6. Inspiring encounters and crucial support

– Parent training: Key to understanding autism

On this path, there have also been wonderful encounters, people who are in the same wake, who bring us tools, knowledge, joy and help.

I’m thinking of Coralie, my son’s educator, who changed our daily lives with behavioral methods, parental guidance and then trained me.

I believe more and more that training parents in behavioral methods is the first step in helping our children.

I’m thinking of Snejina, who opened the doors of her piano class for neuro-atypical people in Paris to me.

Then there’s Christophe and Nathalie, who are the pillars of a parents’ association called the FCPE13. On a daily basis, they provide voluntary help to parents in their struggles, particularly in the preparation of MDPH – key administrative documents that helps those with disabilities get the support they need. This preparation has been no mean feat.

The FCPE13 has become a partner of Piano en Fleurs and has offered to support the creation of l’Enfant Azur in a beautiful garden in Vitrolles.

– The family circle, a common battle

I’m thinking, of course, of my sister, Eglantine Habib, who has also made this her battle as a lawyer specializing in disability, and to close family members who, little by little, have become interested in autism and have looked at and loved my son as he is.

French lawyer Eglantine Habib poses in her office in Marseille, southern France, on November 23, 2021. (Photo by Nicolas TUCAT / AFP)

I couldn’t end this list of wonderful people without mentioning my beloved husband, my daily partner in this adventure.

7. Festival Piano en Fleurs: Neuro-atypical inclusion

I founded the Piano en Fleurs festival in 2020. A rather special piano festival, since since the second edition, we’ve been working on the inclusion of neuro-atypical people and on a joint reflection to make a cultural event inclusive. My team is very aware of neuroatypical, and is very involved in developments within the field. Our shared energy on the subject is contagious.

For the 2023 edition, I wanted to program, among other piano concerts, a show dealing with the subject of neuro atypia aimed at everyone, children and adults alike. As I couldn’t find a show in this vein that spoke to me enough or that resonated with where I was in my knowledge and experience, an idea germinated in my mind: I was going to write and create this show myself.

8. Genesis of “L’Enfant Azur”: an inclusive show

Once I’d come up with the idea, writing became a cathartic necessity. I recalled the particularities of our journey, from the funniest anecdotes to some of the darker moments. It had enough depth and dreamlike qualities to conjure up an initiation tale.

The outlines of L’Enfant Azur began to emerge. The story of a little boy with ASD who learns to know himself, to grow and mature through his differences.

But what would happen if, through this tale, I revealed myself, revealed us?

How can we overcome this prudishness? Paradoxically, through art, isn’t that what we’re looking for at times: to give a voice to little-addressed subjects, and to get involved?

9. Reflections on the meaning of commitment and Autism

– Commitment: another form of modesty

In his work, Thèse dans Temps et Récit, Paul Ricoeur writes

In his work, Thèse dans Temps et Récit, Paul Ricoeur writes

“Time becomes human insofar as it is articulated narratively; in turn, narrative is significant insofar as it draws out features of temporal experience.”

It is through stories and narrative that humanity is constituted and evolves. L’Enfant Azur’s writing is then the act of speaking forth to transform this personal story into that of a universal narrative.

In a second phase, modesty and ego finally give way to the necessity of this creation: it raises awareness of neuro atypia. Commitment takes the place of modesty: using one’s personal history to become an artistic object that engages with a wider reflection.

– Autism and the experience of the Other

Autisme.

Autisme.

Scientists are still in the early stages of understanding this disorder.

In his book Neuro Tribus – Autisme : plaidoyer pour la neurodiversité, Steve Silberman trace the history of autism like an investigative journalist.

From the first diagnosis, to the definition of the word, to the discoveries of neuroscience, to the struggles of mothers throughout history. He also sheds light on what the treatment of this Otherness through history says about societies.

“At a time when the general public was tearing itself apart over vaccines, newly diagnosed adults were launching an entirely different debate on the difficulty of evolving and surviving in a world not made for them. As they recounted their journeys, they discovered that many of the challenges they faced every day were not ‘symptoms’ of autism, but obstacles posed by a society that refuses to consent to the simplest adjustments for people with cognitive disabilities, while making efforts on behalf of people with physical disabilities such as blindness or deafness.

A seemingly simple question began to emerge in my mind: after 70 years of research into autism, why do we still seem to know so little about the subject?”

Disability is merely a potential form of otherness. Invisible handicaps are an otherness that is even more frightening because it seems insidious, since it is invisible: Others who seem so identical in appearance, but who are not so similar. They are like a strange reflection in a distorted mirror.

Unfortunately, I could give many examples of completely inappropriate, even inhuman reactions to my son’s invisible handicap. This bitter experience leads me to believe that the way our societies treat people with invisible disabilities speaks volumes about our relationship with the Other.

The variety of his repetitive behaviors would be a kind of thermometer of our humanity in our societies.

What is Autism if not a spectrum in which normative parameters are listed: the typical functioning of a human brain.

Then, when the cursor on these parameters exceeds a certain norm, the diagnosis is made: you’re autistic. I’d like to say that Steve Silberman’s plea for neurodiversity is also a plea for otherness.

10. Embodying the creative project: voices and bodies

– Moonk, voice and body

Returning to l’Enfant Azur, the text was almost ready to be told.

Returning to l’Enfant Azur, the text was almost ready to be told.

Now the artistic object had to find its form and its voice. I had to find THE person who would embody the voice of Enfant Azur. Someone with a special sensitivity. I was looking for an actor. There were several unsuccessful attempts.

So would it really be an actor who would give his voice?

For a project about neuro atypia, wouldn’t it need a less usual form?

Then I met Moonk. Moonk isn’t an actor, he’s a rapper. He also plays the piano.

He’s a rich, sensitive, creative, enthusiastic and, naturally, an atypical person.

He immediately took hold of the text, made suggestions and embodied this Azur child. Their atypicalities seemed to click.

Moonk narrates, chants, lives, and at times even raps the text. When the text comes out of his mouth, it’s colored by his own light, his own experience, his own visions.

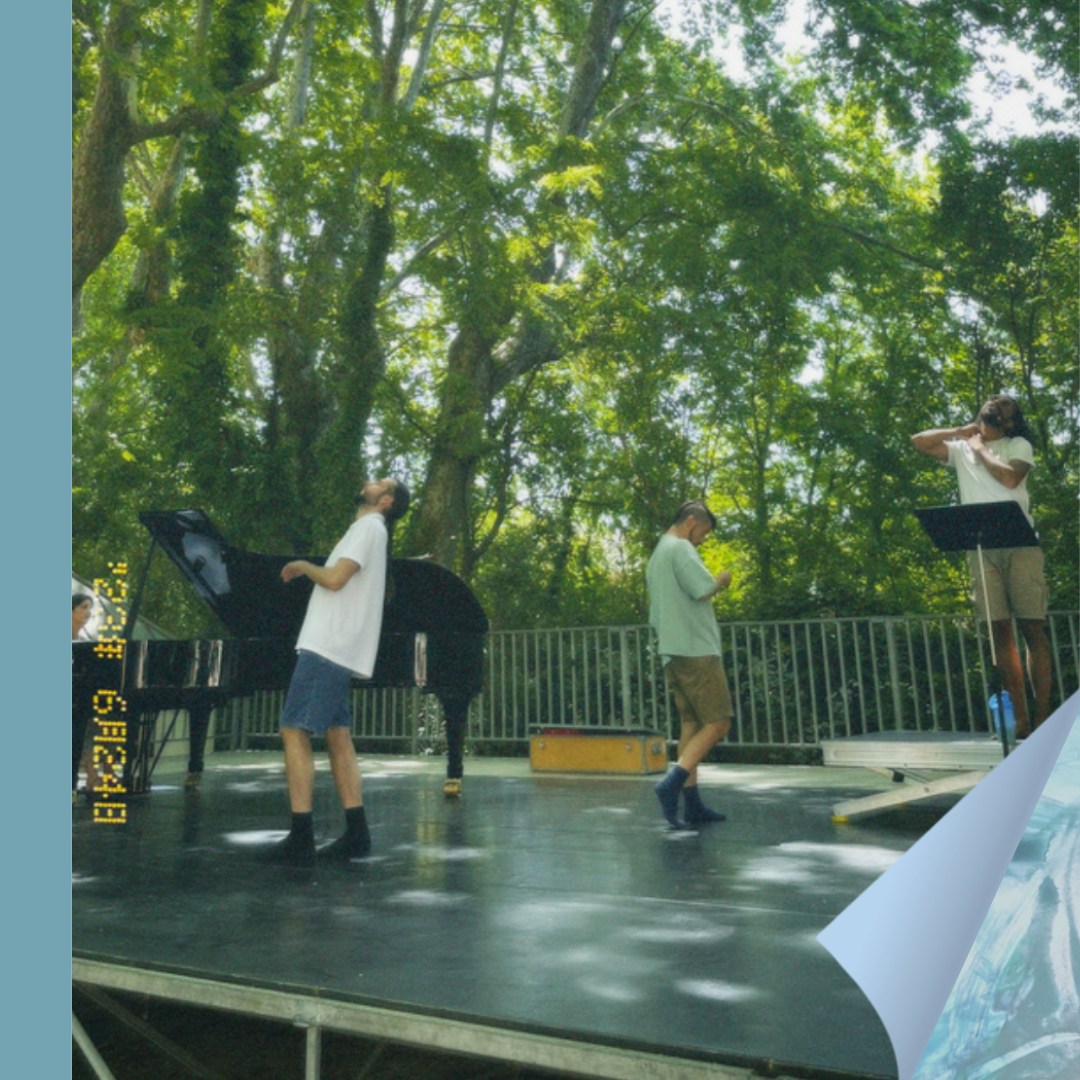

– Angel and Vito, bodies and dance

Vito is an Italian dancer, elegant and precise in his movements. He combines technical skill with creativity. I asked him to join the adventure. Mixing the arts, and incorporating dance, would make perfect sense: movement is yet another vector of understanding and sensitivity, and also tells a story without words.

Vito is an Italian dancer, elegant and precise in his movements. He combines technical skill with creativity. I asked him to join the adventure. Mixing the arts, and incorporating dance, would make perfect sense: movement is yet another vector of understanding and sensitivity, and also tells a story without words.

Vito took some time to think it over, then told me that the theme and story touched him, but that he would take part in the project on condition that they danced in pairs: Angel and Vito. Angel lives up to his name, with gentle, deep-set eyes. His gestures are both thoughtful and free. Angel and Vito recently founded their own dance company, and are used to working on projects and dancing as a duo.

That made four of us.

11. The interdisciplinary creative residency

We began by working as a duo with Moonk. Working sessions at home around the piano, during which we worked out a trajectory between text and music.

We began by working as a duo with Moonk. Working sessions at home around the piano, during which we worked out a trajectory between text and music.

For my part, I selected pieces from the classical repertoire – R. Schumann, JS Bach, F.Chopin, and S.Reich to name a few. I also wrote themes on which I improvised and which correspond to elements of the story: the volcano, the whale, and the people who walk straight.

The four-way encounter took place during an initial residency at the Marseille Conservatoire, followed by another between the Conservatoire and the Ballet de Marseille. Dance added yet another dimension to the project: more visual, it also provided the link, more explicit and, paradoxically, even more poetic.

Little by little, an energy was built up that flowed from one to the other. Nothing took precedence: the scansion of the text, the music and our improvisations all flowed. There was a fluidity between us, an energy bathed in love and kindness.

Together, through our various disciplines and our shared poetry, we told the universal story of difference through the eyes and voice of L’Enfant Azur.

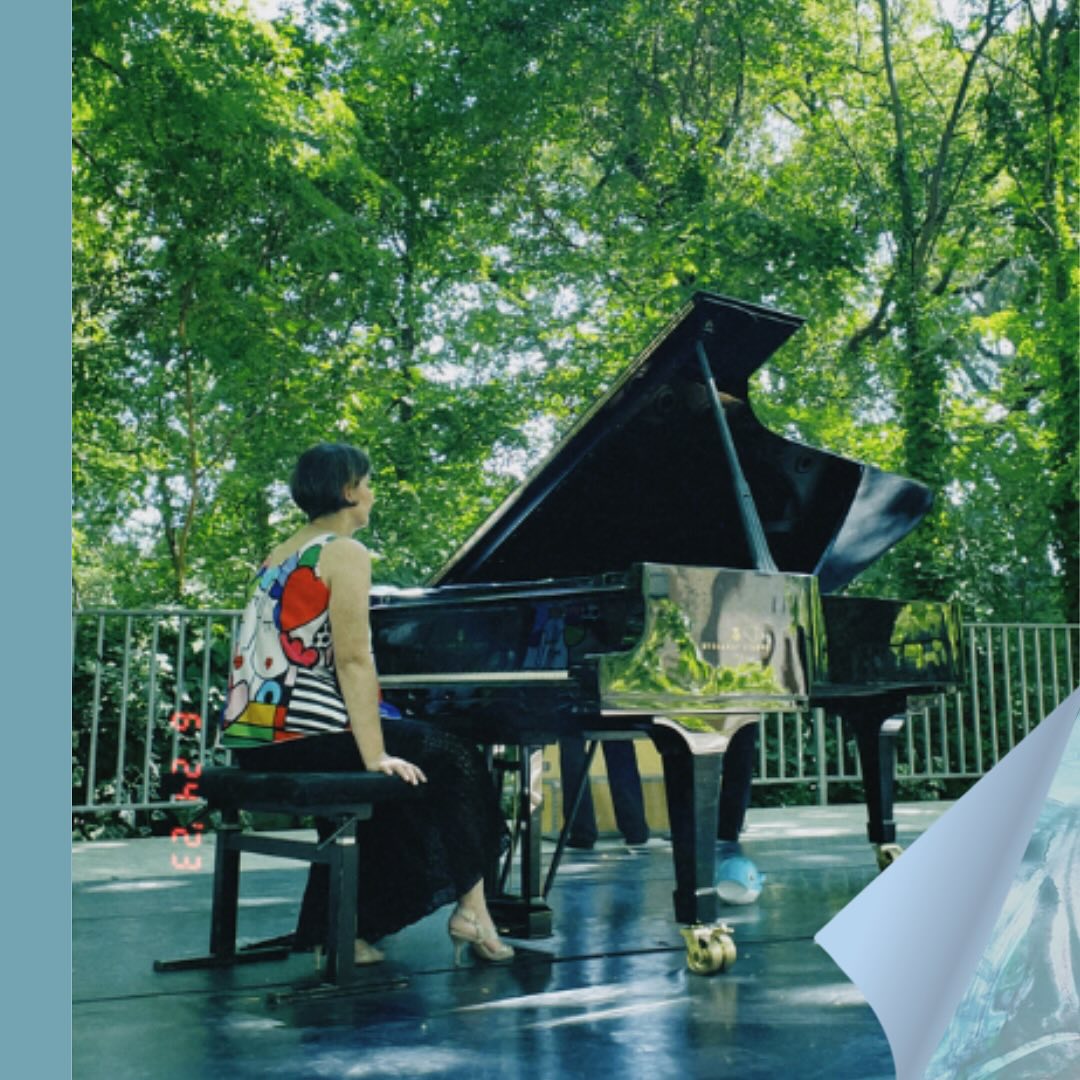

12. The first performance of L’Enfant Azur in the Jardin de Fontblanche, Vitrolles.

Finally, the day of the premiere arrived. We were in the magnificent Jardin de Fontblanche in Vitrolles, on a large stage. The weather was radiant, and the stage and audience were surrounded by magnificent old plane trees. The audience was made up largely of parents affiliated to FCPE13, and we were also expecting families of neuroatypical children.

At our last meeting with Christophe, an administrator from FCPE13, who doesn’t mince his words, he said to me:

“You’re fighting for inclusion. We ask families with neuroatypical children to come to our concerts, but you don’t bring your son to the creation of L’Enfant Azur?”

A few years ago, my husband would take our children to some of my concerts. At an outdoor concert, E. had a fit and wanted to get up on stage with me. From that day on, I decided to continue taking them to concerts, but not to mine.

I thought I was doing it for our own good, but it was mainly to prevent what we call maladjusted behavior from getting out of hand. But isn’t it up to the world to adapt to this disturbance?

Christophe was right, my actions had to follow my words as an activist.

E. would be present, but I hadn’t told him that the subject of the show was his journey.

He stayed with us for a long time in the dressing room just before we went on stage and didn’t want to leave me. I was afraid of a seizure, but when it came time for the show, he sat down with his grandmother and listened attentively. This premiere of L’Enfant Azur moved the audience, made them laugh and transported them.

A few tears rolled down the cheeks of my loyal team, friends and family, the audience and even seasoned performers.

13. Conclusion: Dreaming, laughing and accepting singularity

Campaigning for inclusion is also an internal movement that forces us to rethink our own positions. Despite all the training, reading and commitment we’ve put into it, otherness still questions us and takes us down paths we wouldn’t naturally follow.

Let’s return to the definitions of the notion of the Other and take a detour via the Talmud.

Let’s return to the definitions of the notion of the Other and take a detour via the Talmud.

The Talmud tells the story of a rabbi called Elisha ben Abouya. A great scholar and mystic who became a heretic. Marc-Alain Ouaknine tells and interprets his story in his beautiful book Lire aux éclats.

When Elisha chooses apostasy, he becomes Ahèr, or the Other. Marc-Alain Ouaknine also points out that the word derived from Ahèr is Ahariyout, understood as the quality of being other. This word does not designate otherness, but responsibility. It means being responsible for the other, for the other. We find this notion of responsibility in the law, and in thinking about inclusion. Everyone should feel free, responsible for their own actions and not for the actions of others. But to consider the Other is also to be concerned about his or her well-being.

If we now return to the origin of the word Autism, it was coined in 1911 by Swiss psychiatrist Eugen Bleuler, and derives from the Greek autos meaning “self.” By choosing this word, Eugen Bleuler surely meant a withdrawal into oneself. But if we go back to the Greek meaning of the word, it could also mean that autism is like “oneself.”

This “self,” so similar yet so different. Disturbing too. This definition, a little far-fetched I grant you, takes on a particular color if we return to the normative meaning of autism.

A few final thoughts. In the Talmud, the roots of the word other or otherness are heard in the sound “Ah”: meaning brother, the central fire at the heart of a house, and also meaning to sew – isn’t that right, Tata Christiane? – to take and seize.

L’Enfant Azur in the Jardin de Fontblanche, Vitrolles.

Any powerful human experience forces us to deconstruct ourselves to rebuild ourselves a little differently. The adage that never ceases to resonate: with an extraordinary child, we have an extraordinary everyday life, in every sense of the word. This adage resonates to the point of making us listen to reason. To hear reason in the acceptance of differences. To hear and shout or sing that it’s not up to them to adapt to the world, but up to the world to do what’s necessary to accept their uniqueness.

That day, under the plane trees, we resonated in the same vibration, with the Others, the neurotypicals, the neuroatypicals, in fact, all the Others without finally naming them. The notion of inclusion no longer existed. We didn’t need it, because we were dreaming together.

L’Enfant Azur in the Jardin de Fontblanche, Vitrolles.

At the end of the show, we had an “edge of the stage,” a time for dialogue with the audience. E. joined us, got up on stage and must have recognized himself. This simple yet dizzying moment was full of symbolism. I was a mother with all my heart, but I was also a pianist, a director and all those little strings that held these parts of me together untied to fly elsewhere, perhaps into the world of Enfant Azur.

And it didn’t matter what society might have expected of me, because I traced my voice with the ink and gesture of these facets reunited and liberated.

L’Enfant Azur in the Jardin de Fontblanche, Vitrolles.

This testimony could not end with a period. This reflection is only the beginning, and today it irradiates every sphere of my movements. So, let’s dream, laugh and continue to reflect together with this fantastic quote and definition of the Other by Marc-Alain Ouaknine:

“Having no connection, it is linked to the unknown. He affirms the different, the unexpected. Through his laughter, he shatters all thought that would cultivate the illusion of truth.” Ed: Quai Voltaire, 1989, p50

14. About Amandine Habib

Amandine Habib was born in Marseilles in a family of music lovers. Her father was a jazz fan, her mother had won a first piano prize at the Tunis Conservatory at 18, her grand-parents were keen on opera and on the piano, her great grand-mother played the mandoline while singing Ladino or Yiddish melodies… Thus, Amandine’s DNA is all quavers and appoggiaturas.

Amandine Habib was born in Marseilles in a family of music lovers. Her father was a jazz fan, her mother had won a first piano prize at the Tunis Conservatory at 18, her grand-parents were keen on opera and on the piano, her great grand-mother played the mandoline while singing Ladino or Yiddish melodies… Thus, Amandine’s DNA is all quavers and appoggiaturas.

At 9, Amandine enters the Marseilles Conservatory in Nathalie Lanoë’s class then in Edouard Exerjean’s chambermusic one. In 1998, she obtains two first prizes in both subjects.

In 2002 she is admitted to Bruno Rigutto’s class and gets the Advance Prize in 2006 at the Marseilles’s Conservatory.As an accomplished musician Amandine continues her training by obtaining a University diploma (DEUG) and a degree in musicology. She is very keen on extra- European kinds of music and regularly travels to Laos to study and record the music of the Kammu ethnic group. She gets first class honours for her master’s thesis.

In 2003 Amandine is admitted to the Superior National Music Conservatory of Lyons where she gets the Prize in 2007. She is also involved in pedagogy and obtains her piano Teaching Certificate (CA) in 2013. She manages a career as a concert performer, a soloist and a chamber-music player. As an eclectic pianist, she regularly takes part in creations : Rossini ressuscité, Les Fables de la Fontaine and numerous other of interdisciplinary performances. She performs in a duet with the jazz saxophonist Raphaël Imbert and forms “Kalia”, a duet with soprano Lucile Pessey. She constantly wishes to improve and is advised by famous pianists such as Bernard d’Ascoli, Jay Gottlieb, Bruno Rigutto, Muza Rubackyte and Zhu Xiao Mei.

She is a guest of many festivals : Festival de Musique at Saint Victor’s Abbey in Marseilles, Les Solistes de Demain in Lyons, Musicales du Luberon, Festival International de Piano at Solliès-Pont, Festival International des Nuits Pianistiques of Aix-en-Provence and Marseille Concerts. Amandine regularly gives recitals and public classes in Thaïland in Bangkok and Chiang Mai.